Heavyweight Boxing

Brisbane, Australia - Joe Bugner, the Hungarian-born, British-raised heavyweight who later became “Aussie Joe,” has died in Brisbane at 75. The British Boxing Board of Control confirmed he passed away at a care home, a fittingly quiet exit for a man whose career was lived under the brightest lights and the heaviest expectations.

In recent years Bugner had been living with dementia in a Brisbane nursing facility, a decline widely documented by boxing writers and former colleagues. For a fighter defined by durability, it was a cruel final opponent.

Born József Kreul Bugner in Szőreg, Hungary, in 1950, his family fled following the 1956 uprising, settling in England. A gifted all-round athlete, he grew into a 6-foot-4 heavyweight with a long, educated jab and a temperament more craftsman than brawler. By 1970 he’d beaten the fading Brian London and was a bona-fide prospect; a year later he walked straight into the storm.

On March 16, 1971, in a fight that remains a national argument, the 20-year-old Bugner edged national icon Henry Cooper by the slimmest possible margin — a quarter of a point — to lift the British, Commonwealth, and European titles. That microscopic verdict, and the optics of a beloved champion dropping a farewell decision to a foreign-born upstart, cast a shadow that would trail Bugner for decades.

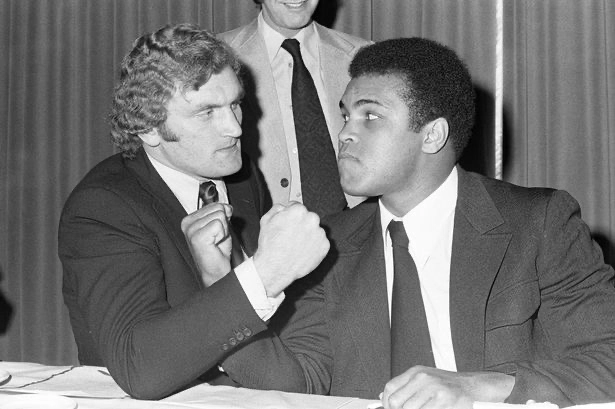

The best heavyweights of the 1970s all had to pass through Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. Bugner did it the hard way — and he finished on his feet. In February 1973 he went 12 rounds with Ali in Las Vegas, conceding a clear points defeat but earning respect for his composure and chin. That summer he lost a decision to Frazier in London. Two years later, in sweltering Kuala Lumpur, he lasted the full 15 in a title shot against Ali, again dropping a unanimous decision. Across those three nights, Bugner logged 27 rounds with the era’s two defining heavyweights without ever being stopped.

The Ali bouts, particularly the second in Malaysia, cemented his reputation: a big, strong, defensively sound heavyweight who wouldn’t give you what you needed — recklessness — to look spectacular. He could be maddeningly pragmatic, a habit that preserved him against the greats and, just as often, cost him on the scorecards and in the court of public opinion.

Bugner never won universal affection in Britain after the Cooper decision, and the perception stuck: too careful, not ruthless enough. Yet the résumé reads differently. He mixed with Earnie Shavers, Ron Lyle, Jimmy Ellis, Chuck Wepner and more, and was consistently among the world’s top heavyweights in the early-to-mid ’70s. He didn’t have Ali’s electricity or Frazier’s relentlessness, but he had a champion’s economy — parry, pivot, touch with the jab, pick the right moments — which is why the best found him so stubborn to shift.

After spurts of retirement, Bugner relocated to Australia in the mid-1980s and re-emerged as “Aussie Joe,” his public image softening in a country that appreciated his old-pro craft and showman’s wink. Not every gamble paid off — Frank Bruno stopped him in eight rounds before 36,000 at White Hart Lane in 1987 — but even that defeat is a marker of his era: Bugner was the man promoters trusted to test the next star in front of enormous audiences.

He wasn’t done. In 1995, at 45, he beat Vince Cervi to win the Australian heavyweight title — evidence of conditioning, stubbornness, and a veteran’s ring sense. Three years later, at 48, he lifted the lightly regarded WBF belt against James “Bonecrusher” Smith on Australia’s Gold Coast, a bout remembered for the right hand that damaged Smith’s shoulder and for Bugner’s improbable late-career belt-lift. He retired for good in 1999 with a professional ledger of 69-13-1 (41 KOs).

Along the way, he picked up solid wins over respected contenders James Tillis and former WBA champion Greg Page — steady reminders that beneath the debates about style and attitude was a very good heavyweight who won real fights against real men.

Bugner was candid over the years about the ambivalence he felt toward fame and the business of boxing. The backlash to Cooper, the zig-zag retirements, the late-life need to keep fighting — all of it spoke to a boxer perpetually negotiating with the game rather than being consumed by it.

The end was unkind. Reports dating back several years detailed advanced dementia and residential care in Brisbane — a fate tragically familiar to too many heavyweights of his generation. The BBBofC’s statement confirming his death at the care home closed the loop, and tributes quickly spanned the three passports he carried in life: Hungarian birth, British prime, Australian reinvention.

If you chased catharsis from Bugner, you often left frustrated — no wild swings, no reckless sieges. But if you watched closely, you saw a heavyweight who understood risk better than most: economical, durable, blessed with a granite temperament and a face that rarely betrayed panic. In the greatest generation of big men, he went the distance with the very best and remained relevant for three decades, from London halls to Merdeka Stadium to the Gold Coast.

He was the “other man” in many famous pictures — Ali’s grin in the humid Malaysian heat; Bruno’s power at Tottenham; Cooper’s furrowed disbelief. Yet pictures lie. The record, and the rounds, tell a tougher truth: Joe Bugner was a world-class heavyweight for a very long time, and that is a high bar in any era.

Farewell, Joe. The giants you stood beside knew exactly who you were.